Menselijke parkbezoekers kennen het park vooral vanaf het droge. Misschien hebben nog weinig mensen het park onderwater gezien. Deze beelden geven een indruk van het perspectief van otters, vissen, water-insecten, en andere aquatische dieren. En laat zien hoe Otterdam er uit ziet voor hen (die ogen hebben).

When the otter came back to our city in winter of 2021, I was quite exited. It seemed like a messenger at a time of extreme drought.

Around that time I was watching ‘The Mandalorian’, a Star Wars series, and in it many planets are visited. As a spaceship tore through the clouds of a distant planet called Sorgan, piloted by the Mandalorian, the audience of this Star Wars tv-show was treated to an impressive feat of worldbuilding.

(Planet Sorgan drawing by Theun)

Immediately striking was the bioregional approach through which this world was envisioned; materials, structures, activities, cultural expressions all were directly derived from intimate connections to a swampy, forested biome. It looked as if the design team had taken the swamp and created an entire swamp culture, including means of living for all kinds of creatures, including people, frogs, fish, algue, shrimp and swamp-robots. This – I thought – is ‘otter-world’, in the sense that the otter seemed like it’s totem animal.

Planet Sorgan appeared here – in a way- as an alternate Netherlands, a reimagined Amsterdam, as a total overhaul of what a contemporary human settlement in a wetland-area might look like. This connected in my mind directly to the return of the otter to our city and eventually resulted in otterdam as a floating garden, not a structure made for otters, but a practice inspired by these iconic waterbeings and their kinship relations. To live in a more active relationship with the waters of Amsterdam. Can’t wait to start on a swamp robot!

Same same but different. Another artist-in-residence has begun. No, not just artist-in-residence, but also work: one thing can mean more than one thing. Just as an expat is also an immigrant. But not all migrants are expats.

Starting today, I will be working for three weeks at the Huiberts biologische bloembollen, an organic bulb farmer in the Netherlands. Here, eight Polish women move from Poland to the Netherlands to live and work for eight weeks in the summer. I would have liked to work with them for eight weeks, but because I had an artist-in-residence in Switzerland and also need time to prepare for the ‘Tulip Mania 2’ residency/exhibition at zone2source starting in September, I only work for four weeks.

As the live-in rooms were full, they even provided me with a camper. I am so grateful. The percentage of organic bulbs is said to be 0.22 per cent of the bulb market, but I wonder if 0.22 percent of people have such kindness. I have a feeling that 0.22 per cent would be too low.

What is my question for this artist-in-residence “cum” seasonal labor? I suppose it is: what do I feel when I actually experience the work? In my research so far, I have talked to industrial relations experts about the precarious working conditions of seasonal workers. In Poland, I also heard about the experiences of people who worked in the Netherlands. It is easy to imagine the labour force of seasonal workers being exploited within the economic structure. However, the quality of working conditions varies. In this organic bulb farm, they are given free accommodation and travel, and their wages are above the minimum wage. However, it is a hard job.

I will soon start work at 7.30 in the morning. I am a little worried about whether my body will be able to cope. But if I can’t do this for such a short period, I’m sure I won’t be able to survive. I can’t even evacuate when a disaster happens. People who are forced to move for unavoidable reasons, such as conflict, persecution or disaster – they are also migrants. I live my life thinking, “I will not be like that”. Although the possibility is not zero.

I’m off to work!

Diary (16th July 2024)

Same same but different. Another artist-in-residence has begun. No, not just artist-in-residence, but also work: one thing can mean more than one thing. Just as an expat is also an immigrant. But not all migrants are expats.

Starting today, I will be working for three weeks at the Huiberts biologische bloembollen, an organic bulb farmer in the Netherlands. Here, eight Polish women move from Poland to the Netherlands to live and work for eight weeks in the summer. I would have liked to work with them for eight weeks, but because I had an artist-in-residence in Switzerland and also need time to prepare for the ‘Tulip Mania 2’ residency/exhibition at zone2source starting in September, I only work for four weeks.

As the live-in rooms were full, they even provided me with a camper. I am so grateful. The percentage of organic bulbs is said to be 0.22 per cent of the bulb market, but I wonder if 0.22 percent of people have such kindness. I have a feeling that 0.22 per cent would be too low.

What is my question for this artist-in-residence “cum” seasonal labor? I suppose it is: what do I feel when I actually experience the work? In my research so far, I have talked to industrial relations experts about the precarious working conditions of seasonal workers. In Poland, I also heard about the experiences of people who worked in the Netherlands. It is easy to imagine the labour force of seasonal workers being exploited within the economic structure. However, the quality of working conditions varies. In this organic bulb farm, they are given free accommodation and travel, and their wages are above the minimum wage. However, it is a hard job.

I will soon start work at 7.30 in the morning. I am a little worried about whether my body will be able to cope. But if I can’t do this for such a short period, I’m sure I won’t be able to survive. I can’t even evacuate when a disaster happens. People who are forced to move for unavoidable reasons, such as conflict, persecution or disaster – they are also migrants. I live my life thinking, “I will not be like that”. Although the possibility is not zero.

I’m off to work!

Diary (17th July 2024)

My first day’s work is to weed around the dahlia’s bulbs. I start working at 7.30am with a group of women from Poland who have come to work. The coffee machine in the kitchen is out of order, so around 6am I head to the office kitchen for a coffee, where John, the owner of this organic flower farm, is already sitting at his computer screen.

Rows and rows of dahlia bulbs are planted in the field. It is completely different from the image of an ‘organic flower farmer’ or ‘multi-product’ in Japan: ‘organic’ but ‘high-tech’, multi -product but ‘mass-produced’. This flower farmer grows bulbs for many flowers, not just tulips. Together with colleagues, we pull weeds using a ‘weed-pulling car’. In that car, five people inside and three outside, lying on beds arranged so that they lie face down, pull weeds around the dahlia bulbs.

‘Meditative work, isn’t it?’ My friend told me when I told him that I would work at an organic flower farm. ‘Is it really? I thought. The weed-pulling car moves automatically, but if you are even slightly worried about which weeds are which, you can’t pull the weeds out at the right speed. In the beginning, Brygida and Kasha, who were sitting beside me, showed me how to do it by hand imitation, and within an hour I was used to the work itself.

I have never seen so many ladybirds in one day, and I am grateful to think that these weeds are also free from pesticides and chemicals. The work, concentrating only on pulling weeds, dahlia leaves, soil and ladybirds, was rather meditative, as my friend said. Although my thoughts of telling my friend that it was better than meditating in Thailand or Bali, and that I would recommend it, were shattered in the afternoon…

Diary (18th July 2024)

In the morning, I wake up to the roosters crowing at around 5am. I can hear the birds chirping incessantly from outside, and on rainy and windy days, the camper shakes so much that I feel the weather on my skin. Just outside, I see John and Johanna’s garden, which is full of flowers in a variety of colours. It looks messy in a way, but it’s probably very well thought out. It’s so beautiful.

The Huiberts has employees working there, not only Polish seasonal workers, but also three interns and many students from the neighbourhood. Summer is the high season, so there are especially many employees. There is a lot of diversity with people from different countries, with different backgrounds and skills.

I share a bathroom and kitchen with three interns, Fenu and Malya, who are from Madagascar and are studying at Réunion, and Heloisa, who is from Brazil. Heloisa studied agriculture in Brazil and her six months in the Netherlands will be over in August. She learned to drive a tractor to dig up bulbs while staying here. ‘The most important thing I learnt here was resilience and patience – when I came to the Netherlands from Brazil in March, it was cold and dark. You have to do physically demanding work every day. It rains a lot. But there was work that had to be done that day, and you put it into action every day. You can study academia at a university, but there were so many things I could only learn here.’ Heloisa told me in the kitchen. You are too good. I have a sore neck from weeding; will there ever be a day when I can learn RESILIENCE and PATIENCE?

Today I weeded the dahlias again. However, as the number of people who could ride in the “weed-pulling car” was limited, I worked in the morning without riding in the car. It’s so much nicer to pull weeds from the ground without riding the “weed-pulling car”. I thought about the Polish women in the car. In the afternoon I got in the car too and pulled the weeds around the dahlias.

Diary (19th July 2024)

Weeding dahlias for three days in a row. I’m here for a tulip project… but it’s good that they are growing so many different types of bulbs. We use the “weed-pulling car” to pull weeds while lying down and looking at the ground. The same position, looking down, puts strain on my neck and shoulders and chin where the bed part hits me. It starts to hurt as soon as I start working.

3FM radio is blaring inside the “weed-pulling car”. When I first visited this organic flower farm some years ago, I was surprised to hear blasting music playing behind the conveyor belts that sort the organic bulbs into sizes. My preconceived notions of ‘organic farm’ and ‘blaring pop songs’ didn’t seem to match.

Today the reason for this loud music became very clear to me. If you don’t get high somewhere, the physical work is hard. I was annoyed when Bob Marley’s laid-back “Everythings Gonna Be Alright” came on. “Singin’: Don’t worry about a thing, Cause every little thing gonna be all right!” I don’t feel like it’s going to be ‘all right!’ at all. Then it was back to dance music, which was somewhat of a relief.

The seasonal workers from Poland are very serious and do not cut corners. They pull the weed at high speed and with great care, using this “weed-pulling car” which the Dutch female employees don’t like to ride. Neither do I, but I do ride and weed.

Diary (20th July 2024)

Yesterday, I worked on the tulip bulbs. Harvesting, weed and soil removal and sizing the bulbs. The harvesting is being done by John and three interns. It is done using two tractors. One tractor digs up the soil surface, harvests the bulbs and returns the soil back to the land. Behind this tractor, there is a place where people can stand on either side, from where they can remove the soil and weeds that this machine could not remove. The bulbs are harvested through an escalator-like arm into a box behind another tractor that runs alongside.

This tractor, which digs up bulbs buried about four times as deep as they are high, is said to cost around EUR 180,000. If rented, with a driver, it is apparently about EUR 200 an hour. Intern Heloisa drives the truck alongside and John drives the tractor that digs up the bulbs. ‘It’s difficult because it has a box on the back and you have to turn the steering wheel the opposite way to driving a normal car.’ I would also like to try driving, but I am not at all sure if I have the right qualities. I did some soil and weed picking behind the tractor. So much dirt and dust.

These harvested bulbs are sprinkled on a machine to remove the excess soil. The soil and weeds are removed by a huge elevator-type machine, and this process is probably repeated several times, followed by the sizing of the bulbs.

Diary (22nd July 2024)

I spent the weekend in Amsterdam and recovered some of my strength. Seasonal workers from Poland work 10 hours during the week and until 3pm on Saturdays. I decided to work eight hours during the week and get Saturday off. I thought I would have a working environment similar to theirs, but it is not at all the same. These women live for eight weeks in a double room, sharing a shower with seven other people, and on top of that, they are courteous and serious about their work. They also seem to enjoy joking with each other while they work.

‘’Do you work on Saturdays, Kumi?‘’ Brigyda asked me, to which I replied that I was going back to Amsterdam. The main reason was that it was too physically demanding, and I wanted to rest, but I made unnecessary excuses such as ‘my husband says he needs a car’.

In Amsterdam, I met some friends. One of them I met, he works as a consultant in the financial sector. He has great respect for producers who make creations from the land. He is aware of ‘the reality that the rights and wealth of certain groups, e.g. white male workers, are realised through the exploitation of another group, people of colour, women or nature’, and he is also interested in food and art, which makes him interesting to talk to. He said that the working environment in the financial consulting industry is poor, and that it is normal to be mentally ill, working 10/12 hours a day on a computer with a budget of 80 Million Euros and enduring power harassment by supervisors…

I don’t think I’m likely to get mentally ill working at this organic bulb farmer, at least for now. I want to get used to it physically as soon as possible.

I am off to work!

Diary (23rd July 2024)

Last night’s dinner was a Japanese curry I had made in Amsterdam over the weekend and brought with me in Tupperware, so all I had to do was heat it up and that was it. Easy peasy. I had curry and rice with Japanese curry roux. Next to me, intern Heloisa was eating white rice and Feijão, Brazilian black bean stew. Malya and Fenu from Madagascar, eat white rice for every meal like I do in Japan, they cooked Katles, Madagascar potato croquettes. The Polish ladies said they were making Polish food. They are making Kotlet mielony, a minced meat dish, and mizeria, a cucumber and yoghurt salad. All sounds delicious.

I feel a bit more relaxed in the second week. Last week, which started with weeding for the dahlia bulbs, was seriously strenuous, but this week it seems easier. We are sorting out the bulbs at the conveyor belt. In the workshop, Polish radio is playing. I’ll write about the detailed work from tomorrow onwards.

Diary (24th July 2024)

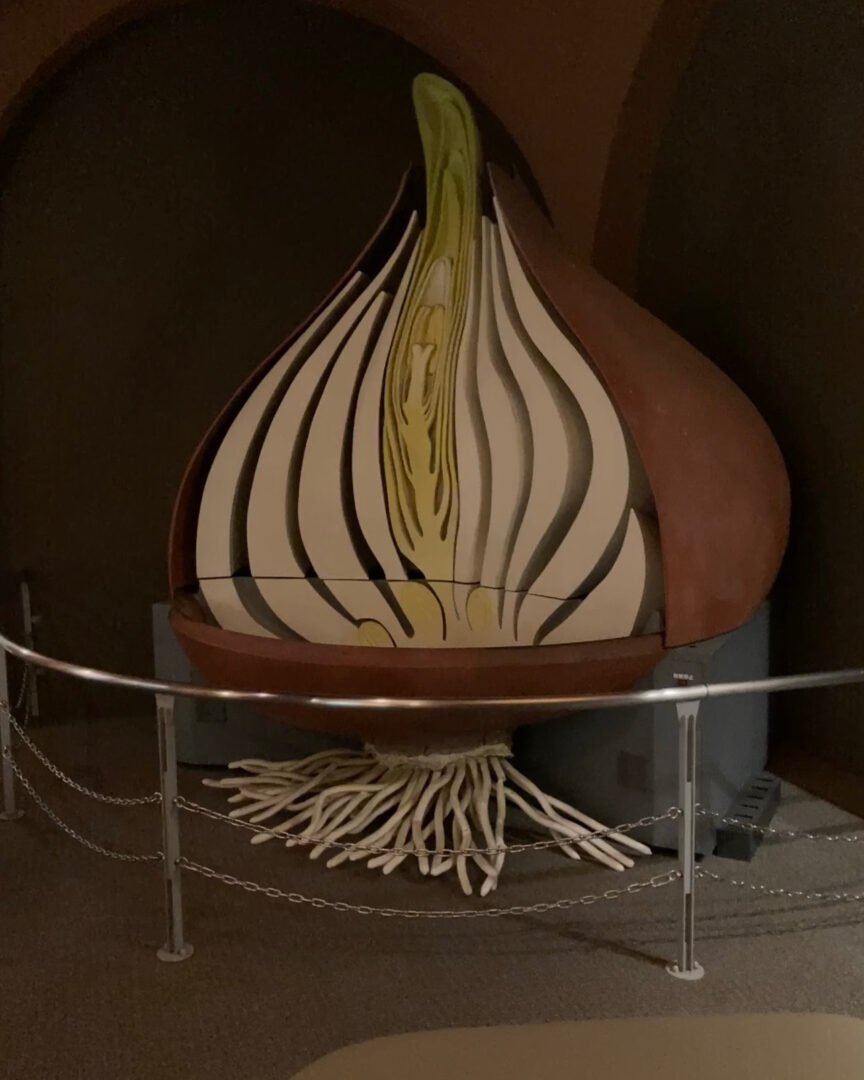

Bulbs, bulbs and bulbs flow before your eyes. To keep up with the speed of the flow, I remove rotten bulbs, weeds and other debris. As I concentrate on this work, I feel as if it is not the conveyor belt in front of me that is moving, but myself. The conveyor belt goes into slow motion, its movement stops and you start moving. My hand follows the bulbs so that I don’t get left behind.

The harvested bulbs are sifted through two types of machines that remove soil and excess roots and weeds. First, thousands of bulbs are placed into a stair-step machine from the top, which sifts out any soil, pebbles, roots, etc. that were not removed during the bulb harvest. The removed bulbs are then transferred to another conveyor belt machine where they are again sieved and sorted by size.

Working alongside the machines, removing soil and roots and sizing the bulbs are part-time students during the summer holidays, live-in seasonal workers from Poland (for eight weeks), Dutch employees and interns.

These bulbs bloom beautifully in the Netherlands. Tulips are symbol of the Netherlands. However, many of the people who work at the site are not Dutch. Here they are Polish seasonal workers. I remember when I visited a tulip cut-flower producer in Poland. Many Ukrainians were migrant workers there.

Diary (25th July 2024)

Quotes from much earlier research because I am tired:

——

While researching flower bulbs, I became interested in the situation of migrant workers from Central and Eastern Europe in the Netherlands and spoke to a specialist, Karin. She works as an associate professor in labour and gender economics at the International Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus University Rotterdam in The Hague, the Netherlands.

Her report “Migrant Labour in Dutch Agriculture: Regulated Precarity” describes the current context in which migrant workers are forced to work long hours for less than minimum wage, and what improvements can be sought. Current employment problems include ‘zero-hour employment contracts’, which stipulate payment only for hours worked and allow workers to be dismissed if there is no work or if they are sick, and ‘package deals’, where labour brokers also provide housing for migrant workers and deduct a disproportionate amount of rent and food costs from the workers’ wages. And this employment problem is structurally supported by consumers who demand cheap goods, and by giant retail chains who are willing to buy produce as cheaply as possible in order to sell their products to these consumers. It concludes that strengthening the union power of migrant workers through awareness-raising and organising is a stepping stone to improving this situation, but it is difficult to challenge the structure behind it, which is to maximise company profits and reduce labour costs. These labour issues are not yet visible from the good employers (farmers) I visit, so this kind of research is very informative and I would like to know more about the current situation.

Diary (26th July 2024)

While dancing, but not so much that people notice, I stand by the conveyor belt and pick weeds off the bulbs as they flow by. To the loud FM radio music coming from behind me.

Reach out with your right hand, then your left. Right hand again, left hand again. Twist your neck, rotate your wrists, and sway your body from side to side as you work. I enjoy playing the choreographer-game alone, thinking about the order in which I move my body. Of course, I’m not skipping picking weeds or separating the bulbs, I’m just making the work dance. Thinking about naming this choreographic work, I remembered that there is a tulip sort called ‘Table dance’. Perhaps ‘Belt Conveyor Dance’ would be a good name. I imagine myself dancing this piece with the Polish female workers around me. No, I am sure I am already dancing with them.

While I was thinking about this, I was called to help with another conveyor belt operation. There, I was working on finishing crocuses. I removed crocus bulbs that didn’t have a nice brown skin on them, and removed the button-like things on the bulbs (what are these? I’ll have to look it up later). Quite a few are removed because they ‘don’t look good’. They must be beautiful when they are bought. The ugly looking bulbs are re-planted in the soil and given a chance to be born beautiful next year. If they don’t come out looking good next year, they will probably be returned to the soil.

With their white, yellow or purple flowers and slender leaves, crocuses are the sign of spring. You were the chosen bulbs that made it through the ‘Belt Conveyor Dance’.

Diary (29th July 2024)

At the weekend, there was a dinner with seasonal workers from Poland, Herman (one of the employees), John and Johanna (the owners) and me.

We went to a Chinese restaurant about 10 minutes away by car, a large restaurant with about 30 tables and a lot of customers. It is an all-you-can-eat restaurant, with a variety of sushi, salads and desserts on the tables. Next to this is the WOK corner, where you can choose your own vegetables, meat and fish, which are then stir-fried in a wok. Drinks are also self-service, but the first drink is poured by John and Johanna, and everyone makes a toast.

They come to this restaurant with John and Johanna every year when their eight weeks of seasonal work is about to end. ‘I didn’t expect to eat Asian food here,’ I typed into google translate and started a conversation with Irena, who was sitting next to me. She recommended sushi and tiger prawns WOK. I followed her recommendation.

Her daughter lives in Germany and showed me pictures. On the beach, a smiling woman and her daughter, who is probably about three years old. ‘I’ll be finished with work in a week. I can’t wait to see my family’, she typed, as she too eats sushi with a fork and knife. Herman is fond of tractors and shows me a photo of his 200 miniature tractors. Some of them are miniature tractors like those used by this bulb farmers. It’s a vocation, Hermann. Johanna and I got into a conversation about swimming therapy with dolphins. As I chewed my sushi rolls, I wondered if other bulb farmers sometimes go out to eat with seasonal workers like this. It’s nice to sit around a table for a meal.

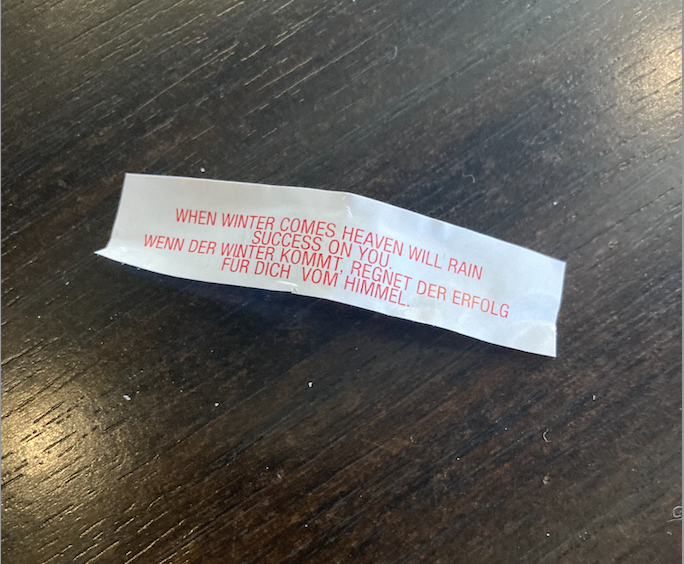

After dinner, Paulina brought fortune cookies for everyone. Mine says “When winter comes heaven will rain success on you.” Heaven, please make it a rain of success. Not just winter rains.

I am off to work!

Diary (30th July 2024)

Here, The Bokashi is made in-house.

Here, The Bokashi is made in-house.

Bokashi is a process that converts organic matter into soil amendment which adds nutrients and improve soil texture. At this farm, the grass from the Zwanenwater Nature Reserve and cow manure from organic daily farmers are fermented by bacteria.

We call it ‘bokashi’ here, but is this cow manure compost? In Brazil they make bokashi without oxygen, that I have heard from Heliosa. Hum…. Further research needed.

Diary (1st Aug 2024)

It is certain that John is the one who works the longest hours during the summer harvest in this organic bulb farm. He always seems to be having fun. Together with Johanna, he is the one of the owners of this organic bulb farm and work from sunrise in the morning until sunset at night, and even on Saturdays.

In the mornings John welds and repairs machines that need repair, prepares shipments in front of the computer, etc., and from 7.30am, when everyone starts working, he drives the tractor to harvest the bulbs and moves the bulb boxes with the forklift truck. Johanna is in charge of PR, marketing, the online shop and accounting, while John works in the workshop and fields. Now that it is summer, the bulbs are harvested, but the work is done all year round: preparing the soil for planting the bulbs, preparing the soil with green manure, making bokashi, planting the bulbs, digging up the bulbs and preparing them for shipping.

John and Johanna see the big picture of how bulbs are produced. The bulbs themselves are the result of a day-by-day process, on top of which the flowers bloom.

This organic bulb farmer owns 70 hectares of land and produces bulbs, which is not large compared to conventional bulb farmers in the Netherlands. Here, it cannot happen that management does not visit the field. The seasonal migrant workers are not exploited with ‘’zero-hour employment contracts‘’ or ‘package deals’, as they are reported in the media. Seasonal workers are paid on the basis of contracts with allowances for holidays and sick leave. The minimum wage in the Netherlands for 2024 is € 13.68 (gross) per hour, but this organic bulb farmer pays € 12.70 (net) per hour, which is € 16.51(gross) per hour when taking into consideration a tax of about 30 per cent.

This wage is the price paid for the repetitive, single task of basically sorting bulbs while listening to blaring music. The bulbs are organic bulbs, no pesticides or chemicals are used and no harm is done to the human body or the environment during the work.

Having been able to work here for a short period of time this time, I felt that it is great that there is no damage not only to the environment, but also to the health of the seasonal workers. I usually buy organic produce, not for taste, but to reduce the environmental footprint. To be honest, I have never felt that the vegetables in the Netherlands taste better because they are organic. However, the advantage of being organic is not only that it is good for the environment, but also that there are no health risks for workers in jobs that are generally considered hard.

Diary (2nd August 2024)

The last day!

Today the polish ladies went back to Poland. On the last day of their eight-week seasonal work, the work finished at 3pm, after which the ladies took a bus to Poland.

My three-week seasonal work cum artist-in-residence is also over. Weekend for now. Cheers for now. Harvesting and shipping is still going on at this huiberts bloembollen. Thank you so much to everyone who has taught me many things there.

The work itself was harder than I had imagined. Somehow, I managed to stay positive, thanks to the good nature of the people who work on this farm.

I think it’s partly because I’m not used to it – my wrists and shoulders hurt, but especially my eyes. Paulina said, ‘When we hand-sort the bulbs on the conveyor belt, my eyes hurt’. When I first started working I thought, ‘why?’, but now I understand. My eyes hurt from looking too much at the huge number of bulbs that flow by. Do we really need such a huge number of bulbs? The market for organic bulbs is said to be 0.22 per cent, and the bulbs shipped from this farmer are only a fraction of the bulbs consumed in the Netherlands. Just thinking of the other 99.78 per cent of bulbs, many of which will be exported, makes my eyes hurt even more.

Will I forget the difficulty of this single task and the pain in my eyes when I see the beautiful flowers in spring? I will not forget. If I were to work next year, I would learn to drive a tractor. For me, looking at the same thing all the time is the hardest part of the work.

At the same time, working on a farm, you never see the same thing. When you go outside and look at a field of bulbs, the plants grow differently every day, every second. And you feel the difference in the weather, the temperature, the wind currents, the length of the day, more sensitively than in the city. It was hard work, riding in the weed-pulling car, but now I’m glad I had the opportunity to work in the field, rather than just repeatedly sorting the bulbs.

To see tulip flowers, you need bulbs. To make bulbs, you need soil. To make soil you need soil organisms. And to sort the bulbs you need migrant workers.

Marlies van Hak in conversation with Tao G. Vrhovec Sambolec

At the finissage of Mind Your Step on November 29th, 2020 Marlies van Hak (researcher and writer) engaged in a walking conversation with artist Tao G. Vrhovec Sambolec (SI/NL), whose work often entails situated interventions related to sound and the step. This performative walk was recorded and edited into an audio document, which is made available here.

Walking-as-Research focuses on walking as artistic and performative research practice, in relation to topical movements in contemporary society. While walking we reflect on the relationship between a moving and sensing body, its surroundings and other bodies. Topics that might pass by are: walking as (situated) research / walking as not-knowing / which or what bodies walk? / what or who sounds or listens? / walking and memory / voids, disruptions, intra-actions / walking as relational and sensorial / walking as protest / how to document walking-as-research?

Visitors where invited to join this performative talk in the Amstelpark, in which the wind in the trees might become a conversation partner and we welcome the unexpected. The discussion will be held in English and could be attended with headphones, in order for everybody to keep distance from one another.

Marlies van Hak’s research focuses on the relationship between art in public space, body, affect and memory. She writes for TAAK and Buro Ruimte Rondom about walking and (collective) memory. As an artist and researcher, Tao G. Vrhovec Sambolec pays specific attention to sound, new media, real-time interaction and questions of contemporary mediation in relation to the sense of (bodily) presence. His recent work consists of spatial and sound installations, events and interventions, in which (un) mediated sonic events, through affect, question the way in which human physical presence can be felt and sensed and what kind of new poetics this can lead to.

Het werk van de Onkruidenier is te zien tijdens Exploded View

Het onderzoek van de Onkruidenier binnen Exploded View bevraagd bestaande kaders die vanuit de ontstaansgeschiedenis van een landschap zijn ontstaan om onze relatie met stadsnatuur te definiëren.

Met de ontstaansgeschiedenis van het Amstelpark in 1972 zijn veel verschillende landschapstypen in de vorm van plantsoenen aangebracht. Dit betekent dat de huidige plantsoenen zijn ingericht als een referentie naar een landschap elders. In het onderzoekstraject van Exploded View zal de Onkruidenier het ‘plantsoen’ als onderzoeksgebied centraal stellen om de relatie tussen mens, plant en landschap te bestuderen. Vanuit deze zienswijzen staan we stil bij de relatie die we hebben met plantsoenen in het park die oorspronkelijk zijn samengesteld als representatie van verschillende landschappen in Nederland en daarbuiten.

Bekijk het werk van de Onkruidenier tijdens Exploded View: parkpresentaties (september 2019) en tijdens de tentoonstelling Exploded View (2020).

Eind 2018 is de Onkruidenier gestart met een vooronderzoek naar de samenstelling van plantsoenen in het Amstelpark. In het bijzonder legden we de focus op de heemtuin. Deze tuin is met meer dan 400 bedreigde plantensoorten aangelegd om kenmerkende inheemse Nederlandse landschapstypologieën onder te brengen in een tuin als educatieve omgeving en daarmee tevens beschermde plantensoorten te waarborgen. Hoeveel van deze plantensoorten hebben zich sindsdien permanent gevestigd in het park, zijn verdwenen of zijn verder verwilderd? Zijn er wellicht andere wilde planten die zich spontaan uitbreiden in de heemtuin? Welke nieuwe balans is er in deze biotoop ontstaan? In hoeverre leiden planten een nomadisch of migrerend bestaan? Welke verhalen vertellen deze planten ons?

Na de Floriade is en blijft de heemtuin zich als geheel transformeren naar een nieuw landschapstype waar nog geen definitie voor bestaat. Uit deze eerste verkenning is een incompleet archief ontstaan dat een beeld schetst van de gevonden gemengde landschappen in de heemtuin. Een drietal ongedefinieerde landschapstypen hebben onze specifieke aandacht getrokken:

Herberg Refugium

De oude muren van ruïne herberg ‘t Kalfje aan de Amstel zijn door de huidige en voormalig ecologisch beheerder van park naar de heemtuin gebracht. Met de restanten van de muur is een nieuwe muur gemaakt die een veilige haven biedt aan Zuid Limburgse kalk vegetatie en allerlei diersoorten. Het is de kalk in het oude cement waar de bijzondere mossen en varens op groeien. Het cement houdt niet alleen de bakstenen bij elkaar het is ook de verbinder in deze nieuwe biotoop.

Wild West Veluwe

Het kruidenrijke rivierdijk landschap heeft in de heemtuin plaats gemaakt voor een zandverstuiving op de Veluwe. Het Amstelpark is zoals nagenoeg alle plekken in Amsterdam opgehoogd met zand. Het park is opgehoogd met pleistoceen zand dat in deze prairie weer vrij spel krijgt door de kolonie konijnen die de vegetatie telkens los graaft. Het landschap vormt een desolate mengelmoes tussen een braakliggend terrein met een vleugje wilde westen. Naast het heerschappij van de konijnenburcht is de teunisbloem de ongekende koningin op dit onstuimige stukje grond.

Maaiveld Bonsai

Een open plek in het bos of een graslandje omgeven door bomen en stuiken. Meerdere malen per jaar wordt dit kruidenrijke landje gemaaid. Door het afvoeren van het afgemaaide materiaal verschraalt de bodem langzaam. Dit handwerk van de beheerders neemt het graaswerk van herten of schapen over. Het doel hierbij is zorgen voor meer biodiversiteit. De maaimachines laten echter een mooi miniatuur spoor achter op het maaiveld. Tal van stompe boompjes, niet veel groter dan een graspol, staan als confetti verspreid in het graslandje.

Deze drie ongedefinieerde landschapstypen gaat de Onkruidenier gedurende het traject van Exploded View voorleggen aan een aantal experts. Kunnen we ze leren duiden of omschrijven als een nieuw type biotoop?

Jonmar van Vlijmen en Ronald Boer zijn de Onkruidenier en leven een niet bestaand beroep. Hun werkpraktijk richt zich op culturele handelingen zoals determineren, classificeren, cultiveren, bereiden en consumeren van wilde planten. Met behulp van veldwerk, artistiek, historisch en landschappelijk onderzoek bevragen ze de relatie tussen mens en natuur. Hun onderzoek ontwikkelt door gebruikers van het landschap als experts te betrekken in hun proces. In hun onderzoeksmatige werkpraktijk staat het experiment naar nieuwe interpretaties van onze relatie met de natuur centraal waarbij de grens tussen cultuur en natuur zou kunnen verdwijnen.

Meer info zie: www.onkruidenier.nl

Presentation Marjolijn Boterenbrood, artist in residence

Glazen Huis | Sunday 15 December, 4 pm

Marjolijn Boterenbrood presents the results of the research into hidden places which she conducted over 2 months in the Amstelpark. She created an alternative map which offers visitors a new way to experience the park. On the windows of the Rietveld House a projection is presented from recordings of the light of the Amstelpark